Teaching Philosophy

Teaching in Religious Studies, not to mention the field of Islamic Studies, presents a host of challenges and rewards. My goal in the classroom is to parochialize students’ own worldviews and presuppositions about religion. This allows us to make the familiar unfamiliar, while avoiding distorting other people’s religious traditions to make them seem more familiar. By the end of the semester, students have facility with the terms and tools through which their own religious or non-religious backgrounds can become newly legible, in conversation with and in light of a broader historico-religious context.

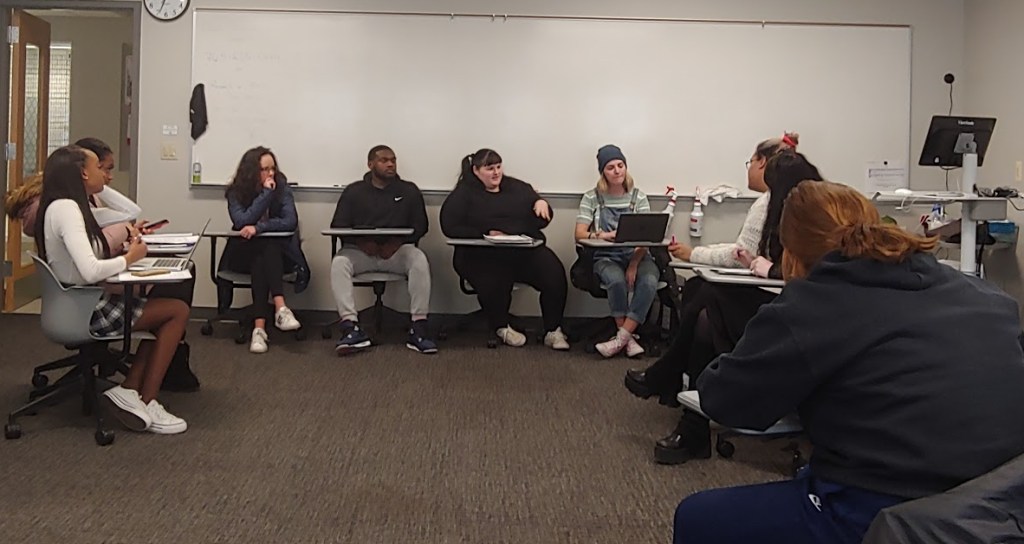

As an undergraduate at Colgate University, I valued small class sizes, intense student-led discussions, and courses that fostered creative and critical thinking. In the classroom, students learn best when they are actively engaged with the course material. This means varying classroom activities regularly, switching between mini-lectures, close-reading, free-writing, brief video clips, small-group conversation, and full-class discussion.

My goal is not to provide students with answers, but with questions and the tools with which to explore and expand on those questions. I organize the class through the use of minimalist Google Slide presentations so students can keep track of where we are in the lesson plan. My teaching style gives students the terms and tools they need to effectively engage with the topic at hand and then immediately asks them to put those tools to use.

Free-writes, pair discussions, and small-group discussions provide students the opportunity to formulate their ideas before sharing them before the whole class. This often encourages them to be more daring or provocative in their thinking than they would be if given less time to organize or formulate their thoughts. Such a teaching style allows shy or quiet students to participate with reduced anxiety, which is why I have nearly 100% participation in most class sessions.

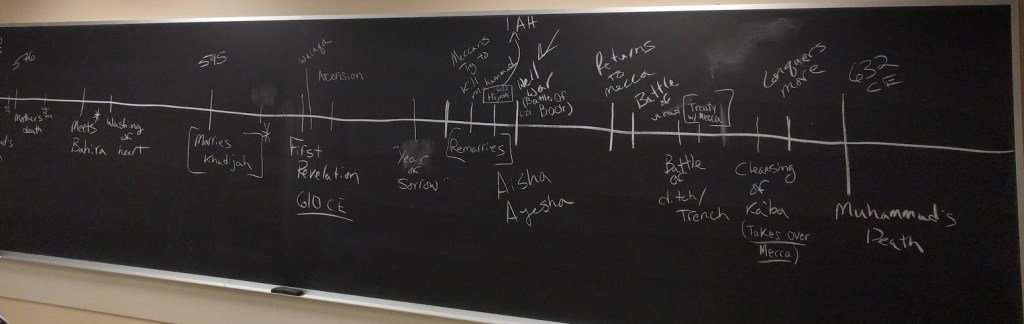

Beyond these traditional classroom activities, I like to invite students to engage more deeply with the material through embodied practice, engagement with material objects, and roleplaying. In RELS 208: The Qur’an and RELS 275: Islam, for example, I ask students to engage with the Qur’an as both an aural and oral text. For one assignment, they are able to attempt to recite, emulating formal recitation styles, either one of the shorter chapters of the Qur’an or the Call to Prayer. In all of my classes, I bring objects from my own research and travels for students to engage with and in every class we visit the David Owsley Museum of Art at least once per semester.

In RELS 160: Religion in Culture, we begin the semester with a mock trial over a variety of First Amendment issues. Students break up into groups and must argue either for or against the inclusion of religious materials in public school curricula or debate the legality of a Ten Commandments monument on public land. This invites students not only to memorize the terms but to apply them in a way that helps them see the real-world applicability of what we are learning in class. Many students come out of this exercise transformed in their opinions about the role of religion in the public sphere and the importance and limitations of First Amendment protections of religion.

Due to the pace of contemporary life and the speed with which students can access data online, I find one of my biggest challenges in the classroom is to get students to slow down. One common gripe of faculty members is that students do not read for class. This may be the case, but I find the bigger problem to be a matter of differing definitions of what constitutes “reading.” One of my goals in student reading and writing assignments is to facilitate careful, critical reading. To this end, in my 100-level courses, I use daily online reading check-in assignments to encourage students to engage with the texts before class.

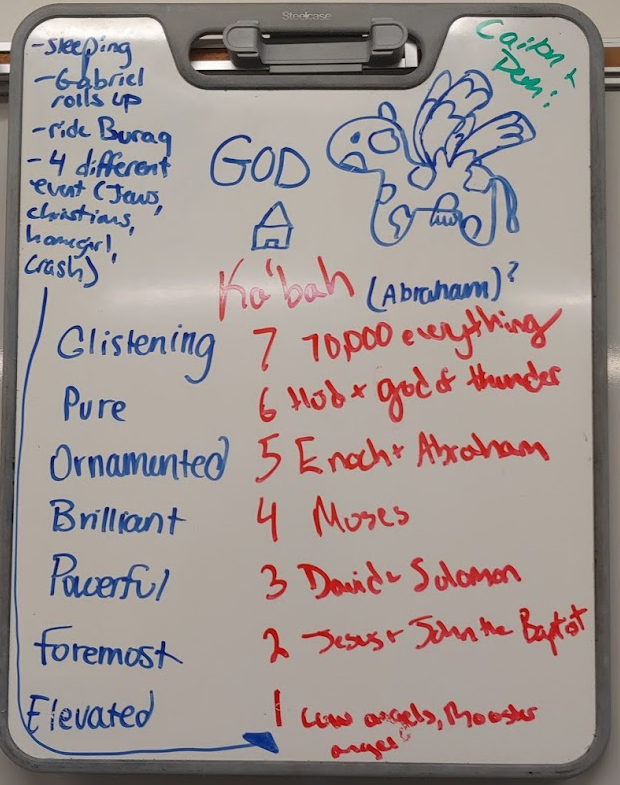

Within the classroom itself, we practice the skills of close, careful reading on multiple occasions throughout the semester. In “Religion in Culture,” for example, we engage in close readings of selections from the Bible and Qur’an, testimonials from Jonestown survivors, and transcripts from a city council meeting in Hamtramck, Michigan. One of the goals of these activities is to get students to set aside what they think they know about Genesis, the Qur’an, Jonestown, or U.S. law and engage with the words on the page. As a class, we read through the passages slowly, discussing translation issues and questions of interpretation. One helpful technique for getting students to slow down as they read is asking them to draw or diagram what they are reading. This technique is particularly effective (and enjoyable) when reading descriptions of Heaven, Hell, supernatural beings, or spiritual journeys.

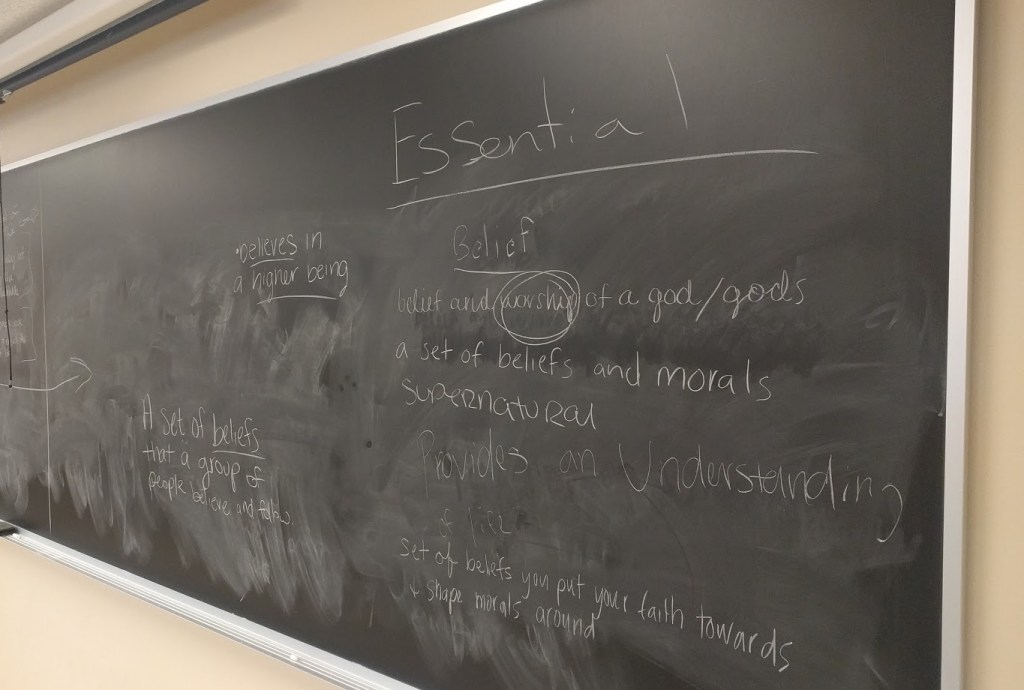

As a teacher, I strive to give students the tools they need to become critical readers, writers, and thinkers. I often tell students that by the end of the semester, they will not learn the “right” answer to the course’s main question (i.e. “What is religion/Islam/the Qur’an?”), but they will be able to identify, analyze, and critique the various possible answers. They do this by learning to read closely, evaluate sources carefully, interrogate their presuppositions, and present their ideas clearly, both in verbal and written form. By extension, my hope is that these skills will help them to become lifelong learners, savvy media consumers, and engaged global citizens.